On-demand mobility is a new and exciting area, promising a world where travel is better, cheaper, faster and safer. Although there are thousands of employees and many billions of dollars being put to work by start-ups and traditional car companies alike, business forecasts appear in the main to be subjective and based on individual intuition. This would make sense in unchartered territory but mass-transportation exists as a business today. It has existed for many decades.

On-demand mobility may change business models and the way travel is experienced, but it is not starting from scratch. People travel trillions of miles each year. There is plentiful data about how they do so.

Our key findings are as follows:

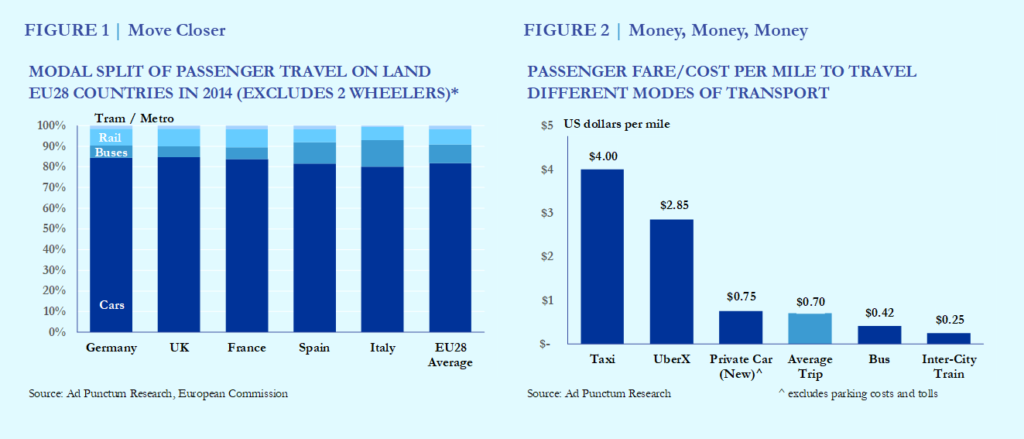

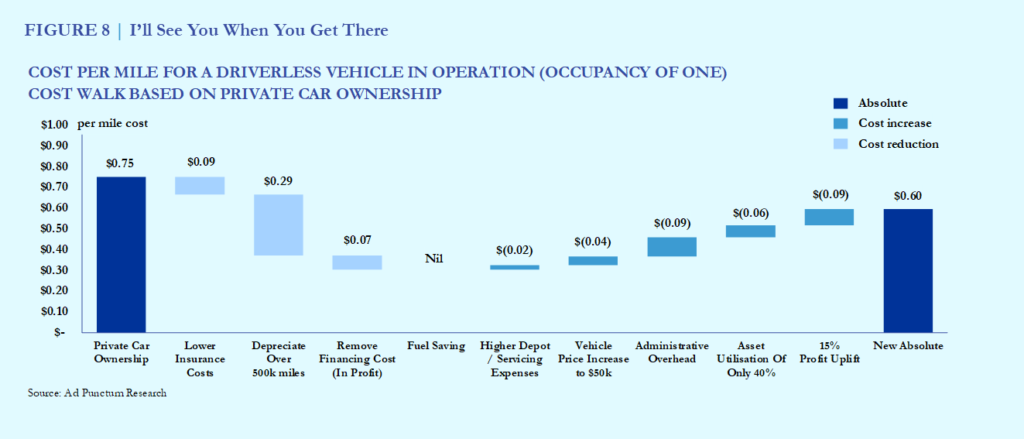

- Current average spending on land-based travel is about $0.70 per mile — the figure is slightly higher in the US and a little lower in the EU28. This is the share of spending that on-demand mobility companies are competing for. Although some modes of transport (e.g. public buses and rail) are substantially cheaper than cars, this does not meaningfully skew the average because of the dominance of the passenger car for land travel

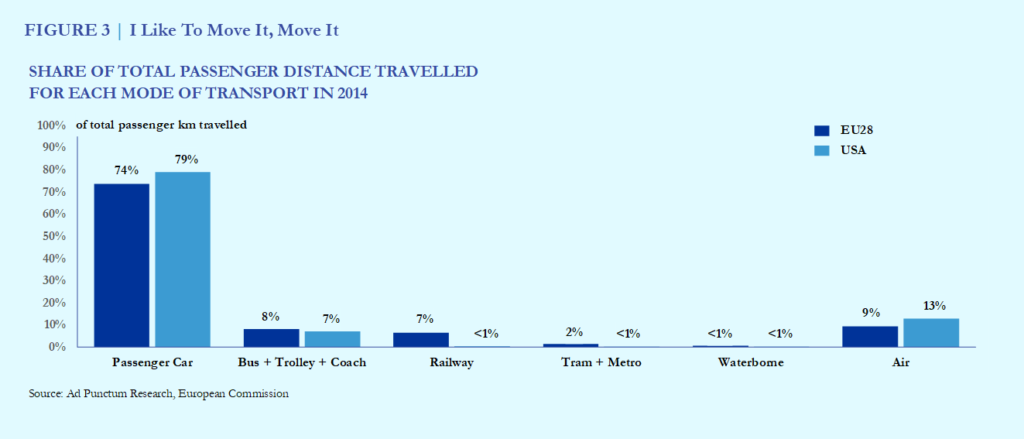

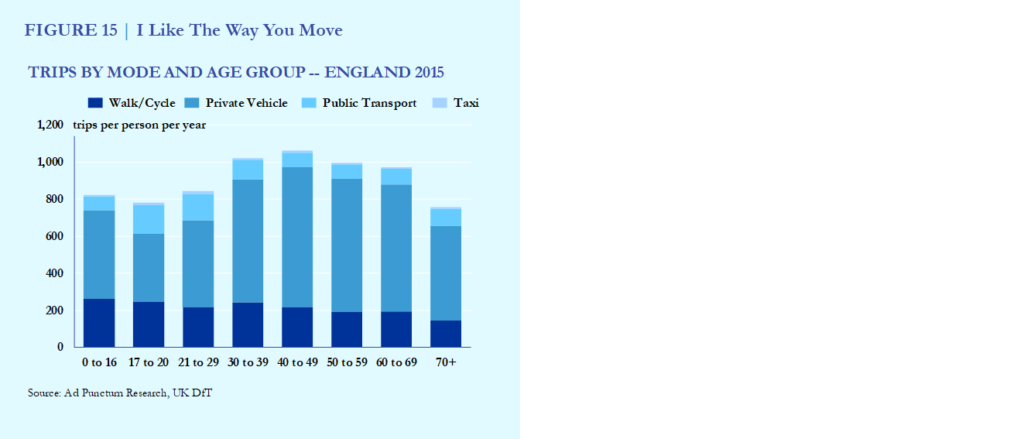

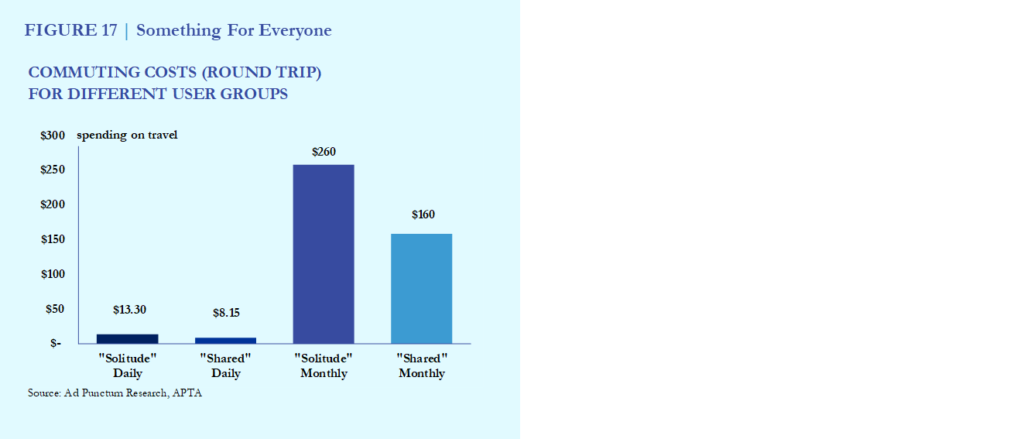

- Any big switch to on-demand travel isn’t coming from rail, bus and air — it comes from car ownership. The clear majority of passenger miles travelled are already by privately-owned car. Whilst there is potential for transfer from other sources (e.g. buses) and creating incremental travel, our analysis is that this amounts to between 15% – 25% of the market. Most on-demand revenue comes from people subscribing to a service that covers all their travel needs rather than buying a car.

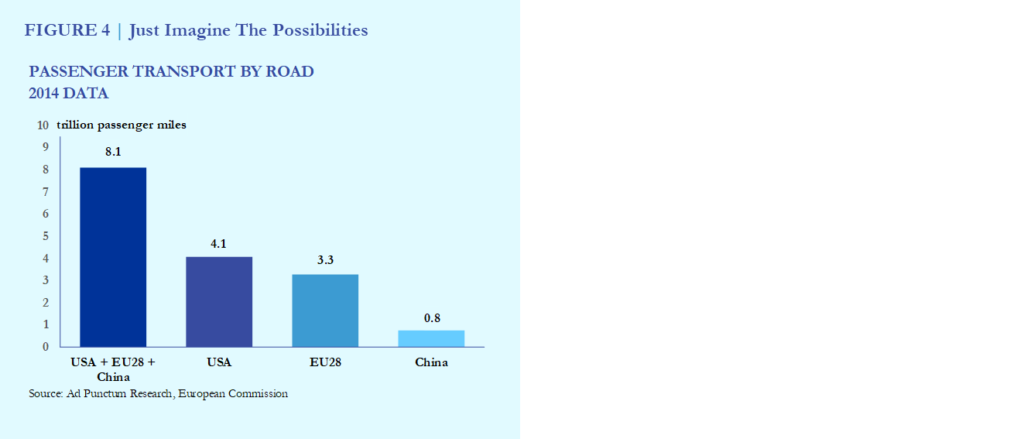

- The potential revenue of a wholesale switch to on-demand is huge — $6 trillion per year. Already the population of the EU, USA and China collectively travel more than 8 trillion miles annually, a figure that will increase through economic growth. Changing from private car ownership to on-demand unlocks that revenue without even changing travel behaviour.

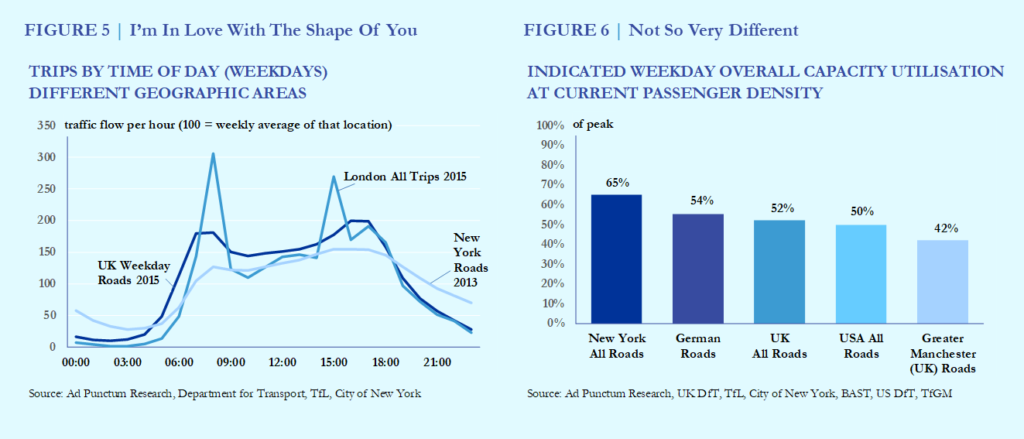

- Establishing a viable on-demand model faces a big problem — capacity utilisation. The pattern of “rush hours” holds across different regions and countries. Utilisation assumptions above 50% are optimistic. Without sufficient capacity, people won’t give up their cars. If they don’t do that, on-demand struggles for market share.

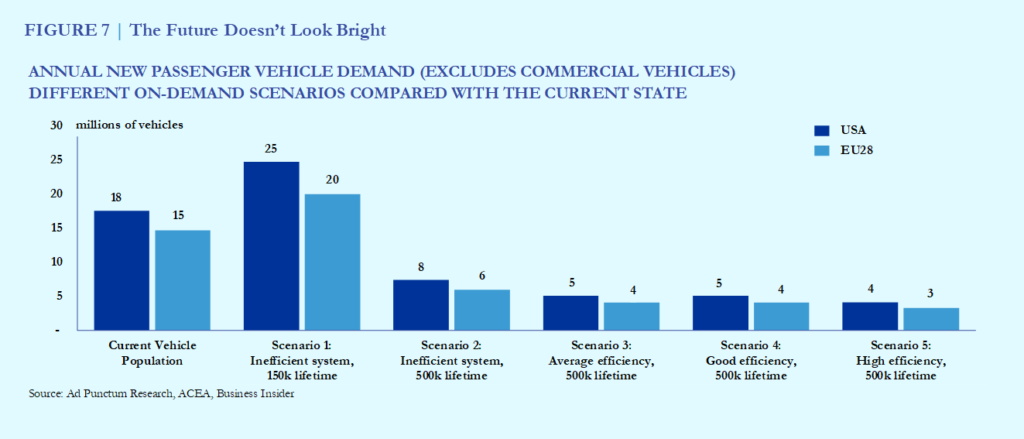

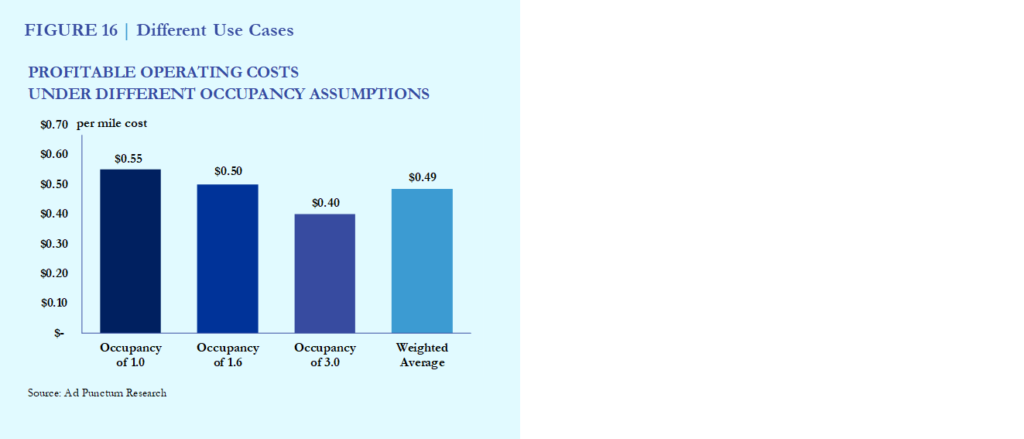

- Driverless on-demand services can achieve prices of $0.60 per mile and below even without sharing and will dramatically reduce car production — by between 60% – 75%. The privately-owned car is so inefficient in terms of utilisation that even lower-end assumptions for system efficiency drastically reduce the number of new cars needed.

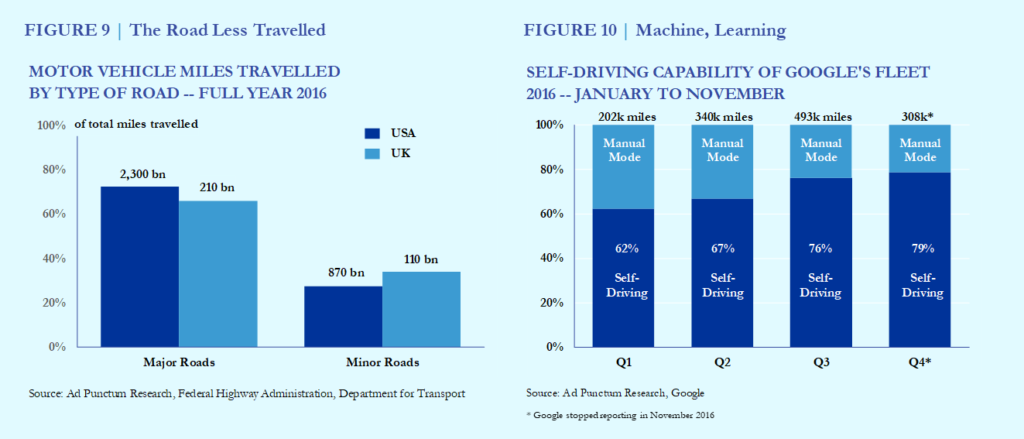

- Autonomous vehicles will be capable of most journeys sooner than many people think — by the early 2020s. The classic driverless test is a narrow urban road filled with perils but this is a rarity, not a day-to-day reality, for most journeys. Around 70% of travel in the USA and UK is on major arterial roads and highways — the technology is nearly capable of this now. Driverless cars don’t need to be capable on 100% of routes to capture share. The network will grow road-by-road, just like cable TV.

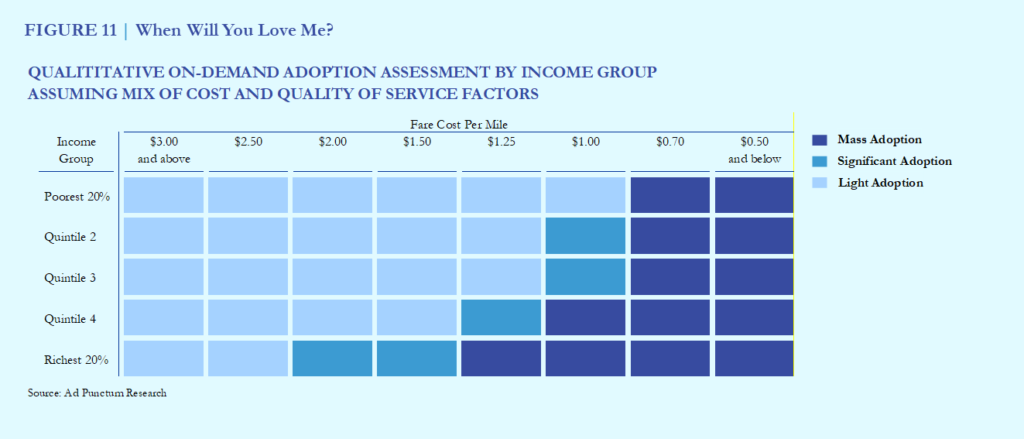

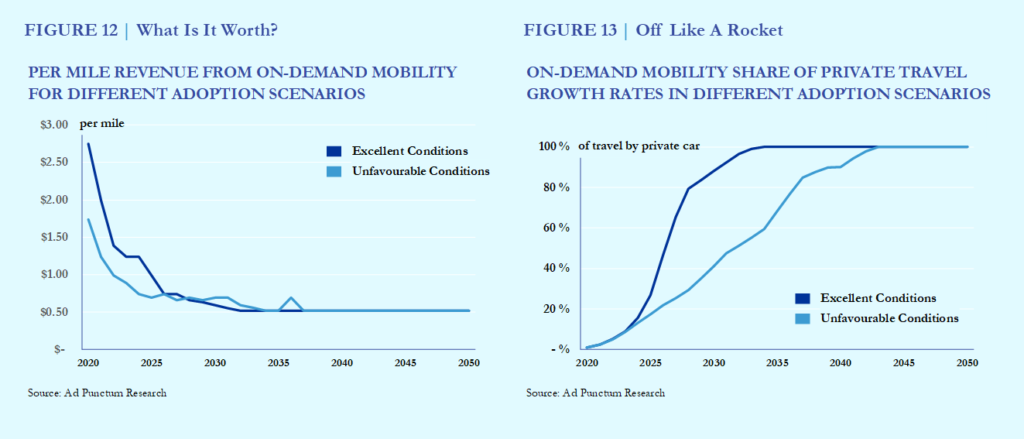

- Widespread autonomy will be with us by 2030 — accounting for at least 40% of mileage. The rate of switchover depends on three things: price, technology and regulation. The rate at which taxis win share as price drops has been studied for many decades. Taxis win share slowly and it is only the rich who can afford to pay extra. If you look at it from Uber’s point of view, growth seems meteoric but this is from a very low percentage of travel in taxis (about 1% of trips) to a larger but still very low percentage of travel via ride-hailing. Reaching cost parity with car ownership creates a dramatic consumer response. Favourable regulation and technology progress could double the rate of adoption (to over 80% in 2030). This level of growth may not require a colossal amount of upfront funding — cash flow is hugely positive since revenue is still related to taxi services with human drivers (albeit with discounts) but costs are far lower.

- Regulators have a substantial role in the rate of adoption. It isn’t sufficient for driverless cars to be good enough, they must also be legal. Regulators aren’t in universal agreement on what is good and bad about “dumb” cars today; myriad different laws, technical standards and tax rates attest to that. Expect autonomous vehicles to create even more regulatory misalignment. The upshot will be that those who are favourable to driverless on-demand mobility, and control access to significant markets, may shape the fundamental industry model and technical standards. It may not be the “best” technical delivery of an autonomous vehicle that becomes widespread, it could be the one that was most convincing to those governing the streets of California, London and Singapore. A very likely manifestation is that successful operating models will be ones that regulators see as win-win situations. For instance, a fleet that is entirely battery-electric. They will also shape operating details such as how fast a vehicle can drive in certain circumstances (manufacturers will struggle to justify that their vehicles are fool proof in freezing conditions) and whether it is the passengers or a remote control centre that takes over the vehicle if the automatic systems fail.

- Autonomy will struggle to take public transport’s 15% share whilst fares are above $0.40 per mile. Once this level is reached, the 15% or so of public transport customers could switch. Public transport loses money but it keeps fares low at the point of use and more than half of its customers are price sensitive. Without an innovation that transfers the existing public transport subsidy to on-demand customers on a means-tested basis, they will wait for a lower fare level before switching.

- The increase in travel from people less restricted than today is likely between 5% – 10%. Increased freedom for those with restricted mobility will be welcome but will not substantially change the fleet mileage because they are a relative minority in the population and they already travel today (albeit less frequently than average).

- Travel at $0.40 per mile is within reach. It might not even require special vehicles. Although research work continues into on-demand vehicles with capacities of 10 people and above, this may remain in the domain of pure academia. A system carrying an average of three people at a time could still be profitable and use the same vehicles for solitary customers paying a higher price.

- A price structure similar to UberX versus UberPool is likely to persist. Creating a single fare level ignores some of the fundamental dynamics of human choice. In general, people don’t like to share if they can afford it. Therefore, it is more likely that richer people will choose to pay more to ride alone or with close family and friends.

- Governments are going to face some tough decisions on public transport eventually. If on-demand services can match the $0.40 per mile price point as we forecast then customers will adopt on-demand due to its lower overall travel time, door-to-door service and additional convenience (“remember the olden days when we actually used to stand in the bus?”). This will be a mixed blessing for governments. On the one hand, they can remove the substantial subsidies currently paid to public transport operators. On the other, vested interests (those losing their jobs — from station masters to route-planning bureaucrats) and political idealists (who hate the idea of the private sector running transport) will lobby not to abandon public provision of services. They will have more success in some countries and cities than others.

What does this mean? The adoption of on-demand mobility is going to depend primarily on cost as long as regulators don’t get in the way. Although adoption scenarios vary in timing by a decade due to variation in regulatory and consumer preference, there is a route to $0.40 per mile across regions. Mass adoption will considerably reduce vehicle sales, so for carmakers the exact timing is academic — they should begin planning for massive capacity reduction. An industrial purchasing base may support fewer brands too (aircraft, oil service suppliers, mobile phone infrastructure builders point in this direction). Suppliers will worry too. For everyone else? Chauffeurs for all (in time)! Catch up on sleep, start a food blog for pets or maybe just take in the scenery.